“In a context of deep regional instability, the situation of the “frozen conflicts” is vulnerable to Russia’s military presence and the unpredictability of its geostrategic actions…”

Russian military aggression against Ukraine has a profoundly detrimental impact on the sustainability of Russia’s geostrategic interests in virtually the entire ex-Soviet space. Members of the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) and the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) are reassessing their relations with the Russian side. This is determined by the “devaluation” of Russia’s geopolitical reputation, as well as the spread of the effects of Western sanctions on the trading partners of the Russian state.

One exception to this trend is Belarus, which, since the crackdown on post-election protests against Lukashenko in 2020, has been completely sucked into the orbit of Russian influence. Likewise, the geo-economic opportunism of the current Georgian government based on the intensification of economic ties with Russia leaves room for negative interpretations. At the same time, while condemning the occupation of 20% of their national territory (Abkhazia and South Ossetia) by Russia, the Georgian authorities promote policies, such as the “foreign agents law” (Euronews, February 2023), which bring the country closest to the Russian or Azeri authoritarian standards. This deviation risks weakening Georgian democratic institutions and compromising European integration efforts. In other cases, the states of Eastern Europe (Ukraine and Moldova), the South Caucasus (Armenia and Azerbaijan), and Central Asia demonstrated unfavorable movements for Russian geopolitical positions.

With increasing uncertainties for Russia in the context of its aggression against Ukraine, cracks are appearing in the status quo surrounding “frozen conflicts” in the ex-Soviet space. While the situation in Abkhazia and South Ossetia is under Russian control, in the case of the Transnistrian conflict (Moldova) and the Armenian-Azerbaijani dispute over Nagorno-Karabakh (Azerbaijan), things are complicated for Russia. Transnistrian separatist elites are forced by the circumstances of the war to accept arrangements with the Moldovan constitutional authorities (mutually acceptable) to ensure their political and socio-economic survivability. This growing reliance of the Transnistrian separatist regime on decisions in Chisinau cripples Russia’s room for maneuver. While understanding the potential costs to the separatist regime, Moscow is seeking to exploit the Russian military presence in the Transnistria region in its information warfare against Ukraine and Moldova. The situation is different in Nagorno-Karabakh, where under pressure from Azeri attempts to restore territorial integrity, the Russian peacekeeping mission is facing a serious image crisis in Armenia (Reuters, January 2023). Without Azerbaijani-Armenian political support, Russia may lose its strategic utility to Armenia, where public demand is already growing for an international peacekeeping mission to replace the Russian one. Therefore Russian positions on these two “frozen conflicts” are strongly eroded and contested, and the success of the planned Ukrainian counteroffensive in 2023 may further degrade Moscow’s situation and its influence on these conflicts.

Russia’s geopolitical reputation crisis

Two parallel processes affect Russian strategic interests in relation to states where the Russian language remains the lingua franca. On the one hand, there is a growing interest in increasing economic sovereignty vis-à-vis Russia. And, on the other hand, there is political emancipation and an attempt to get out of the geopolitical shadow of Russia, pursuing in some cases the objective of diversifying the sources of security.

In the first case, the Central Asian states are looking for ways to strengthen ties with the EU and the US. Reducing reliance on Russian critical infrastructure and building energy sovereignty are areas of common interest with the EU. European decision-makers are determined to invest in projects that would connect the Central Asian region with pan-European transport and energy routes (Euroactiv, November 2022). In this sense, through the European global platform (Global Gateway), with a budget of about €300,000mn, the EU enters into an undeclared competition with Russia and China for influence in Central Asia.

The second process concerns Armenia and Azerbaijan, which, together with Ukraine, Moldova, and Georgia, joined the European Political Community (EPC) launched in Prague in October 2022. Russia’s decoupling from the EU in the context of Russia’s war against Ukraine represents a “window of opportunity” for Armenia, which has expanded dialogue with the EU beyond the realm of security. With the contribution of France, the Armenian side agreed with the EU on the deployment of a civilian mission in Armenia (EUMA), which began operating on Armenian territory in February. Yerevan will have to establish a political-diplomatic balance so that EUMA co-exists with the forces of the Russian military base, active in Armenia since 1992. Azerbaijan’s eye is on strengthening the energy dialogue with the EU, which would give it access to the European market, which seeks fresh supplies of natural gas to replace imports from Russia. To prevent future episodes of gas weaponization, the EU reduced pipeline deliveries of Russian gas to below 10% in October-November 2022 (from 40% of total imports in 2021). Increasing its forceful role in the strategic calculations of Brussels, Baku eclipses sensitive issues related to the persecution of the opposition or civil society. The gas could help the Azeri government expand its ranks of friends in Europe. The EU seems to ignore the scandals related to cross-border political corruption within the Council of Europe ($2.9bn in bribes), with accusations about the involvement of the Azeri side.

The examples discussed above show that the weakening of Russian geopolitical relevance in regions previously considered to be under Russian influence motivates regional state actors to diversify the balance of power, appealing to the EU and other Western actors.

Nagorno-Karabakh: complications for Russia’s positioning

Established as a result of tripartite agreements brokered by Russian leader Vladimir Putin in November 2020, the Russian peacekeeping mission (1,960 soldiers) in Nagorno-Karabakh is on the brink of disrepute due to its inability to ensure the functioning of the Lachin Corridor. Starting in mid-December 2022, the Azeri authorities, under the pretext of environmental protests, blocked the normal operation of the Lachin corridor. This route is essential for the transport of people and goods between Armenia and the separatist region. In the first phase of the blockade, the Russian peacekeepers were equally responsible for blocking the route. However, following the action taken by the International Court of Justice (UN) this February, only Azerbaijan is qualified as the party responsible for preventing access to Nagorno-Karabakh (ICJ, February 2022). Both the EU and some member states, as well as the US, are putting pressure on Baku to implement the UN court’s request, exacerbating the humanitarian crisis in the breakaway region populated mainly by ethnic Armenians.

In the context of the refusal of the Azerbaijani side to fully restore the connection between Armenia and the Armenian population of Nagorno-Karabakh, the Russian peacekeepers do not appear to be involved in the forced unblocking of the Lachin corridor. In a wait-and-see position and under Armenian public pressure, Russia avoids making moves that favour either side and are detrimental to its balancing act. In Russia’s calculations, the need to keep its blue helmets in the region after the expiration of the mandate in 2025 prevails. Ensuring an effective peacekeeping mission does not exactly correspond to this Russian objective.

FOR THE MOST IMPORTANT NEWS, SUBSCRIBE TO OUR TELEGRAM CHANNEL!

The fragile balance around the region and, respectively, the state of the Russian peacekeepers depends on the actions of the Azerbaijani side, whose stated strategic goal is to seize control of Nagorno-Karabakh. Baku insists that Armenia would use Lachin to supply weapons to Nagorno-Karabakh, which violates the trilateral agreements negotiated with Russia in 2020-2021. Under this pretext, the Azerbaijani authorities demand the installation of a customs checkpoint on the border with Armenia, at the entrance to the Lachin corridor (Interfax, March 2023). Without this corridor, the breakaway region cannot survive, and Azerbaijan taking control of this critical infrastructure would increase Armenia’s reliance on Russian peacekeepers. One way for Yerevan to expand its playing field against Moscow and Baku would be for the EU to establish a border assistance mission at the entrance to Lachin, similar to the EUBAM Mission in the Transnistria segment. Such a mission would help manage the flows between Armenia and the population in the separatist region, with the participation of the Armenian and Azeri parties, without Russian mediation.

Russian scenarios for the Transnistrian region

Concerns about the destabilization of the breakaway region of Moldova (Transnistria) have returned to public attention after Russia circulated unsubstantiated accusations that the Ukrainian authorities were planning a military attack. Deputy Prime Minister for Reintegration of Moldova Oleg Serebrean rejected any scenario in which Chisinau and Kyiv would co-ordinate a military intervention in Transnistria. At the same time, the Moldovan authorities recognize the legitimacy of the Ukrainian decision to strengthen its military presence along the Transnistrian segment to protect itself from Russian threats.

The risks related to Russia’s ability to arm the Transnistrian region, with or without the separatist regime’s knowledge, for tactical objectives in the war in Ukraine or to increase instability in Moldova are real. In the spring of 2022, Russian security services were suspected of orchestrating a series of low-impact explosions on critical infrastructure in Transnistria (Riddle, May 2022). The separatist administration in Tiraspol claims that it will not abandon neutrality in the face of the situation in Ukraine. At the same time, the region’s political and economic elites follow Moscow’s instructions, giving them leverage in negotiations with the constitutional authorities in Chisinau. For this reason, although it may increase tensions on the border with Ukraine, the administration in Tiraspol wants to carry out military exercises together with the Russian peacekeepers, in the months of March-May.

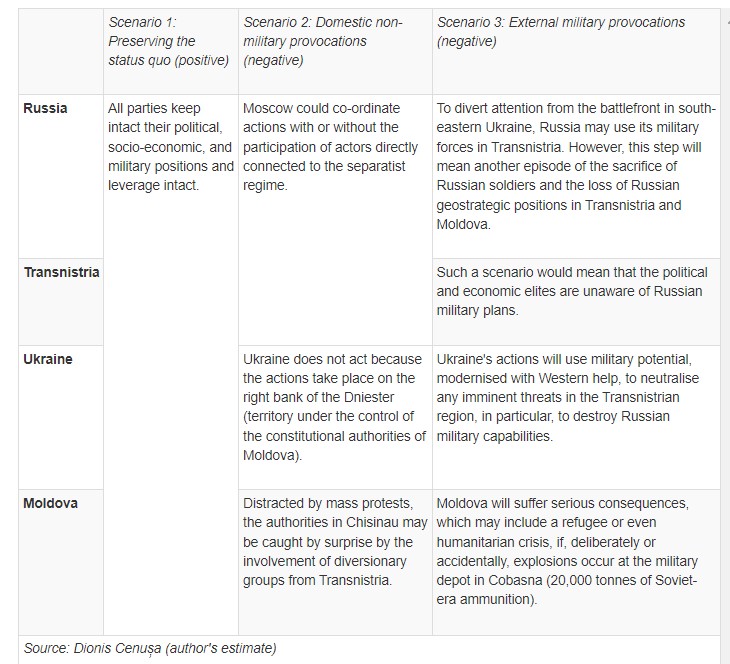

The evolution of the situation around the Transnistrian region can be examined through the lens of three main scenarios. The most positive scenario is the “preservation of the status quo” (scenario 1), which assumes that the Transnistrian region remains neutral in order to keep existing channels open for foreign trade. Russia has its status in the region intact, and Ukraine and Moldova continue to monitor the situation in Transnistria to prevent escalations. The second major scenario that must be taken into account is the case in which Russia uses the material and human resources of the Transnistrian region to carry out non-military provocations on the territory of Moldova. This scenario is useful for Russia only if it decides to support subversive actions against the Moldovan constitutional authorities. If the protests by the populist opposition with Russian connections get out of control and seek to change the constitutional order, Russian implementers of subversive operators, based in Transnistria, will most likely be called in. The third scenario refers to the great challenges facing the Russian military forces located in the region. The target of the provocations would be Ukraine, but the main costs of such a decision by Moscow will be borne by the Transnistrian region and Moldova. This would include the destruction of critical infrastructure in Transnistria, with implications for the safety of the military depot at Cobasna, and a refugee crisis in Moldova. For now, the prevailing scenario foresees the preservation of the current situation, but, in case of radical changes in the situation in Ukraine and Moldova, it will be necessary to draw attention to the other two (see Table below).

In lieu of conclusions…

The efficiency of the Ukrainian defense and the Western cohesion in articulating comprehensive sanctions against Russia had a destructive impact on Russia’s geopolitical supremacy in the ex-Soviet space. Paradoxically, Russian diplomacy has reached a point where it is more effective in dealing with states in the Global South than with countries in its immediate neighborhood.

The deterioration of Russian-Ukrainian ties is irreversible as a result of Russia’s war of mass destruction against the Ukrainian state and its people. Although worsened by energy blackmail, Russia’s dialogue with Moldova will depend on future Moldovan political conjunctures. The South Caucasus and Central Asia are exploiting Russia’s geopolitical weaknesses to develop geo-economic and geo-strategic alternatives with the participation of the West. While Belarus is a satellite controlled by Moscow, Georgia walks on the edge of the cliff, risking its credibility due to the opportunism of the ruling elites.

In a context of deep regional instability, the situation of “frozen conflicts” is vulnerable to Russia’s military presence and the unpredictability of its geostrategic actions. Both Nagorno-Karabakh and the Transnistrian conflict may become victims of Russia’s unfortunate strategic and tactical calculations and decisions, either accidentally or deliberately, with repercussions for regional security.

This article was written by Denis Cenusa for Intellinews.